Public Housing: An Architectural Challenge

What are the most important aspects that designers should consider in residential buildings?

A house that is not simultaneously a home is an unfinished design. The necessity for shelter as a place that provides protection against exterior forces, where one can feel safe while carrying out day-to-day activities is indisputable. However, a home, particularly one designed for the modern man, cannot be reduced to such a primitive objective. To have a home is to have a personal setting that allows users the freedom and space to live according to their own personalities, preferences, and unique needs. It is ‘a place where a harmonious family life develops together with the relations between its members. This is not possible where space is so cramped that its occupants are constantly falling over each other’ (Berry, 1974, p.2).

The key questions of interior design must revolve around the needs of the future inhabitants, that, in a residential building might be, for instance, a family of four. When it comes to public housing, the process becomes more complex. The designer must anticipate the needs of the inhabitants as part of a diverse spectrum in terms of gender, ethnicity, age, number of family members, etc. Dwellings cannot be planned on the idea of a universal user, an endless repetition of a fixed layout; they need to be planned as multiple solutions to different life scenarios. This essay is going to discuss the challenges of public housing in the post-war French and British context and mainly focus on three important aspects of their design: the well-being of the occupants in terms of physical and mental comfort, flexibility and durability, and communication between the dwellings and the surroundings.

The consequent background of the two World Wars was characterized by destruction, shortages of every kind, and an overall feeling of fear and confusion. Europe faced a housing crisis that manifested as major overcrowding and the unresolved prominence of ‘slums’ - dwellings that were deemed inadequate for habitation. This led, in effect, to ‘rebuilding’ the continent. The dreadful atmosphere gradually decreased as people acknowledged the opportunity to leave behind an obsolete world and replace it with a new, promising one. ‘There was a feeling that society was at a nexus, that the future was in the hands of the post-war generation… Architects considered themselves one of the groups in society most responsible for forging the plans for the future’ (Webster, Modernism Without Rhetoric: Essays on the Work of Alison and Peter Smithson, 1997), but they had to go through trial and a great deal of error before reaching sustainable results.

For the French, the solution was building tall ‘concrete cordons’ around the peripheries of big cities. Their goal was to be cheap and fast to build (using prefabricated elements) and most of all, to fit as many dwellings as possible. More than just concrete blocks, these ‘villes nouvelles’ (new towns) were supposed to be self-sufficient in the climate of the undeveloped outskirt surroundings and were planned to have their own public amenities such as shops, schools, and clinics. However, this idea wasn’t a sudden spark of architectural ingenuity, but rather an adapted version of the mass housing prototype Unité d ‘habitation by Le Corbusier in 1952. The project failed as a sustainable construction, but it represents one of the first viable concepts in modern social housing and a landmark for the following buildings of the sort.

One of the first ‘villes nouvelles’ projects was the Sarcelles apartment building during 1955-1970 by Roger Boileau Jacques and Henri Labourdette. What differentiates it from other social housings is that, despite its immediate popularity, after a few years of being inhabited, the overall opinion was scandalous- ‘chicken cages’, ‘ghetto towns’, ‘resembling a concentration camp’. Although experimentally, it introduced a few social features, the design lacked crucial elements such as leisure facilities and public transportation and it was completely isolated from the urban areas. These aspects led to pathological symptoms such as claustrophobia, depression, and other mental health issues, furthermore causing disturbing behavior in young people.

The social tower blocks of Modernism were an architectural disaster, an ‘inflexible and inhumane treatment of urban space and its outright denial of people’s needs and aspirations’ (Cupers, The Social Project: Housing Postwar France, 2014). However, prefabrication and the use of concrete remain sustainable means of construction due to their fair proportionality between cost and quality. Being aware of the potential of these inexpensive construction treasures, French Post-Modernist architect Jean Nouvel, took his chance at the ever-challenging field of architecture which is public housing. His goals were to design a cost-effective building with spacious, well-lit, flexible dwellings, thus ‘shaking off the bad karma attached to the housing problem’ (Boissiere, Jean Nouvel, 1997).

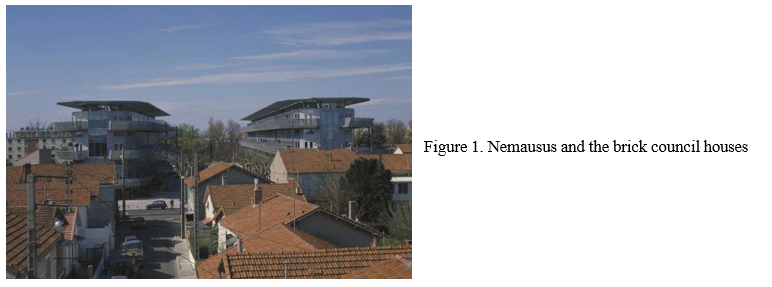

Built between 1985-1987, Jean Nouvel’s Nemausus 1 project portrays a futuristic approach to residential architecture. Designed as parallel buildings that resemble two naval ships due to their proportion and use of industrial materials, it emerges from the outdated and contrasting landscape of low-level council housings (Fig. 1). The site is located in the Mediterranean city of Nîmes and offers a gentle climate and the perk of outdoor living. The dialogue between the site and the buildings is depicted by the big balconies placed on the sunny southwest side, accessible through the living room’s tall folding doors, and by the large leveled sidewalks on the northeast side. The space is consistent with the way people really live, it allows room for human behavior to unfold. The sidewalks are not just simple means of access, but social environments that create the atmosphere of ‘the streets’ – children playing, and riding bikes. It is a transparent design that welcomes human interaction.

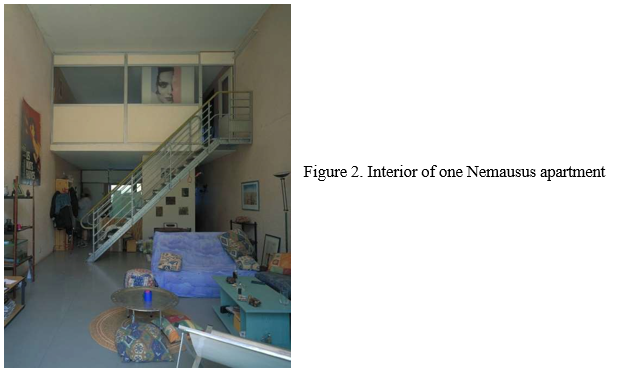

Though It was intended for the working class and was given a moderate budget, Jean Nouvel did not compromise on the quality of the design and followed the ‘basic but forgotten principles’ (Jean Nouvel). The main principle was based on the idea that ‘a good apartment is a big apartment’(Jean Nouvel). All dwellings have a surface of at least sixty square meters but what makes the space airy and full of light is the lack of constrictions such as unnecessary partition walls, and the open space (Fig 2). More than that, the design covers the essential aspect of flexibility. As architect Jean Nouvel explains his work: ‘Nemausus means the architecture doesn’t stop at the front door: these apartments are all designed with specific spatial layouts and scenographies’. The dwellings are divided into 17 different interior solutions for different potential inhabitants with different needs.

The Nemausus project is a monument for the history of mass housing, a successful attempt at applying the principles of interior design with cost-effectiveness consideration. It is a statement of the true ‘condition of architecture’ which is ‘the direct confrontation between culture and society and the site’ (Boissiere, Jean Nouvel, 1997).

France and Britain ‘shared remarkably similar ideas about the virtues of planning and mass housing' (The social project: Housing Postwar France). Much like France, Britain was a victim of the war that struggled with shortages and shelter. With the hope of slowly but surely increasing the economy of the kingdom, people were encouraged not to waste any material but to try and reuse, repair, and recreate during the ‘Make Do and Mend’ campaign. This conservation spirit triggered the idea of house prefabrication as a fast and cheap solution to cope with housing demands. ‘Why not switch these factories over to the production of houses, using the light, efficient, and beautiful materials, like steel duralumin, and light alloys, which are stretched to such efficiency and economy in aircraft’ (Donald Gibson, 1940).

In 1944, a Temporary Housing Act was passed with the scope of producing as many shelters, faster and cheaper than the classic Victorian houses. The population was excited; the buildings had a futuristic appearance; there was a sense of modernism that was attractive to young families. All buildings had integrated appliances such as fridges and washing machines which were considered an extravagance for most people, who not long ago were deprived of minimum sanitary conditions. However, the project was an experimental solution to the pressing conditions. The hopes for the effective building were demolished as the project turned out to be a lot more expensive than anticipated and the quality of the construction was low-grade. The walls were poorly isolated, leaving room for moisture and cold which led to a negative impact on the health of the inhabitants.

With regards to the housing situation of the 50s’, publisher Robert Maxwell states: ‘We believed that if his (Le Corbusier’s) ideas were followed, the world would not only have better architecture but would be a better place’. Le Corbusier’s principles transcended regional architecture and guided the design of modernist and post-modernist social housing on a larger, international scale. For British architects Alison and Peter Smithson, The Unité d'habitation in Marseille portrayed, at the time, a similar vision to their brutalist ideas and a prototype for their future housing project. Its blunt language of rough, unfinished concrete and the repetition of architectural elements were the basic principles of the New Brutalist concept introduced by the Smithsons in the 50s. Fundamentally, it relies on exposing the materials of the construction ‘as they are’, showing ‘the woodiness of the wood; the sandiness of sand’ (Smithson and Smithson, 1990, p. 201). From a conceptual point of view, ‘it faces up to social relations, critically handling them in built form, and exposing, not hiding its limitations and contradictions.’ (Thoburn, 2018, p. 617)

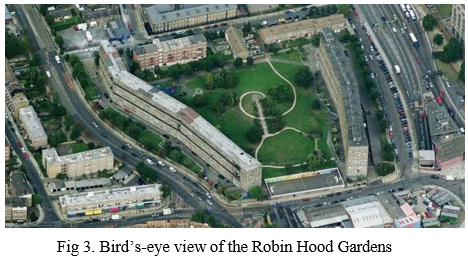

Alison and Peter Smithson’s Robin Hood Gardens was built between 1968-1972 in a similar layout to the previously mentioned building - Nemausus 1 by Jean Nouvel; two distinct concrete buildings in terms of surface shape that shelter a green, leisure zone (Fig. 3). It was located on the East side of London, near the River Thames in an industrial environment. The choice of the site is not arbitrary, and it is strongly connected to the brutalist ideals of the architects; Alison Smithson stated about the character of the location as being ‘forthright and honest’ (Smithson in Johnson, Smithsons on Housing, short film, 1970). What is noteworthy about the design is the efficient communication between the building and the surroundings and the way it adapts to the neighboring impediments. The industrial tone of the site and the fact that it is surrounded by motorways creates heavily disturbing background noise. However, the complex is cleverly protected by tall concrete walls placed near the roads that conflict with the outside noise, and each building is directly shielded by vertical rectangular elements placed on the length of the walls with the same purpose of sound insulation.

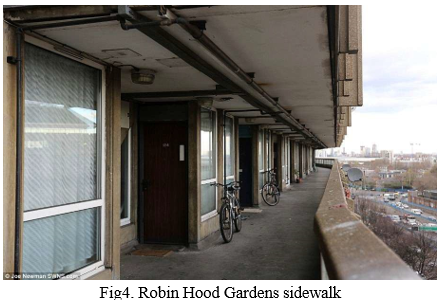

Aside from the technical aspects, the architects also considered the social condition. The design was intended for the working class, but it is distant from the idea of cramped, depressing spaces. Dwellings range from one to four-bedroom layouts, depending on the needs of each future inhabitant; they are spacious, airy, and filled with natural light. The communal spaces of the buildings are designed in a way that people can connect and form communities, similar to Nemausus 1. The decks are wide and offer the necessary space for inhabitants to socialize, carry out activities, and at the same time leave enough room for people to use the sidewalks as means of access. The interior, intimate space, though, is protected from the communal areas by extending the entrance of the dwellings onto the decks (Figure 4) so the occupant’s ‘doormat is not kicked aside by the passers-by’ (Smithson in Johnson, Smithsons on Housing, short film, 1970).

The Smithsons’s goal, in this context of post-war architecture, was to design a sustainable building that would last for the next generations and consequently, help to create a ‘pool of housing from which people can choose how to live, where they want to live’ (Smithson in Johnson, Smithsons on Housing, short film, 1970). Ultimately, the scheme failed and was deemed a concrete monstrosity; however, interviews of the occupants show that the environment was enjoyable and easy to live in

Residential architects build not for the sake of aesthetics, but to offer future occupants a space where they can feel secluded from any dangers and enjoy everyday life in comfort. Regardless of the financial, political, and environmental limitations, they have an obligation to provide a scene in which every potential inhabitant can make themselves ‘at home’. As shown in this essay, there is no set of rules one can follow in order to achieve these results. The criteria are not constant, they depend on the ever-changing spirit of society. Architecture cannot be confined to the ideals of one certain period in time and, most of all, it cannot be based on a universal user’s needs.

Through their housing designs, architects Alison and Peter Smithson and Jean Nouvel, demonstrated an understanding of residential architecture’s true scope, which is to anticipate and resolve distinct living scenarios.

References

Berry, Charles Knight. Housing; The Great British Failure. 1974, p. 2.

Cupers, Pieter. The Social Project: Housing Postwar France. University of Minnesota Press, 2014.

Gibson, Donald. Architect, 1940.

Maxwell, Robert. Articles on Le Corbusier, 2004.

Smithson, Alison and Peter. "The ‘As Found’ and the ‘Found’." In The Independent Group: Postwar Britain and the Aesthetics of Plenty, edited by D. Robbins, 1990, pp. 201–202.

Smithson, Alison and Peter. The Smithsons on Housing, short film by B. S. Johnson, 1970.

Thoburn, Nicholas. "Concrete and council housing." City, 2018, p. 617.

Webster, Helen. Modernism Without Rhetoric: Essays on the Work of Alison and Peter Smithson. John Wiley & Sons Inc, 1997.

Cupers, Pieter. The Social Project: Housing Postwar France. University of Minnesota Press, 2014.

Gibson, Donald. Architect, 1940.

Maxwell, Robert. Articles on Le Corbusier, 2004.

Smithson, Alison and Peter. "The ‘As Found’ and the ‘Found’." In The Independent Group: Postwar Britain and the Aesthetics of Plenty, edited by D. Robbins, 1990, pp. 201–202.

Smithson, Alison and Peter. The Smithsons on Housing, short film by B. S. Johnson, 1970.

Thoburn, Nicholas. "Concrete and council housing." City, 2018, p. 617.

Webster, Helen. Modernism Without Rhetoric: Essays on the Work of Alison and Peter Smithson. John Wiley & Sons Inc, 1997.

Image sources:

Fig 1. http://www.jeannouvel.com/en/projects/nemausus/ Access date: 11.04.2019

Fig2. http://www.jeannouvel.com/en/projects/nemausus/ Access date: 11.04.2019

Fig3.https://www.arquitecturayempresa.es/sites/default/files/content/arquitectura_robin_hood_gardens_ae rea_smithsons_0.jpg Access date: 11.04.2019

Fig4. https://i.dailymail.co.uk/i/pix/2017/04/26/21/3F9D803100000578-4447906- Robin_Hood_Gardens_in_Poplar_It_was_built_as_a_council_housing_e-a-83_1493238626804.jpg Access date: 11.04.2019

Bibliography:

Millais, Malcolm. "A Critical Appraisal Of The Design, Construction And Influence Of The Unité D’habitation, Marseilles, France." Journal Of Architecture And Urbanism, 2015.

Grindrod, John. Concretopia. Old Street Publishing, 2013.

Till, Jeremy and Tatjana Schneider. "Flexible Housing: The Means To The End." Architectural Research Quarterly, vol. 9, no. 3-4, September 2005, pp. 287-296. © Cambridge University Press.

Berry, Fred. Housing: The Great British Failure. Charles Knight & Co. Ltd., 1974.

Boissière, Olivier. Jean Nouvel. Publisher: Birkhäuser, 1996. Revised Edition.

Morgan, Conway Lloyd. Jean Nouvel: The Elements Of Architecture. London: Thames & Hudson, 1998.

Røstvik, Harald N. "Mass Housing And Sustainability." Open House International, vol. 38, issue 3, 2013, pp. 31-38.

Curtis, William J. R. Modern Architecture Since 1900. London: Phaidon, 2013. Third Edition, Revised, Expanded, and Redesigned.

Webster, Helena (ed.). Modernism Without Rhetoric: Essays On The Work Of Alison And Peter Smithson. London: Academy Editions, 1997.

Calder, Barnabas. Raw Concrete: The Beauty Of Brutalism. William Heinemann, London, 2016.

Monacelli, The Charged Void: Urbanism, Alison And Peter Smithson. New York: Monacelli, 2005.

Bertho, Raphaële. The Grands Ensembles, Fifty Years Of French Political Fiction. Société Française De Photographie Printed Version, 2014.

Jackson, Anthony. The Politics Of Architecture: A History Of Modern Architecture In Britain. London: Architectural Press, 1970.

Cupers, Kenny. The Social Project: Housing Postwar France. Univ of Minnesota Press, 2014.

Urban, Florian. Tower And Slab: Histories Of Global Mass Housing. Routledge, 1st edition, 2011.

Smithson, Alison and Peter. Without Rhetoric- An Architectural Aesthetic. Latimer New Dimensions Limited, 1973.